By John M. Flora

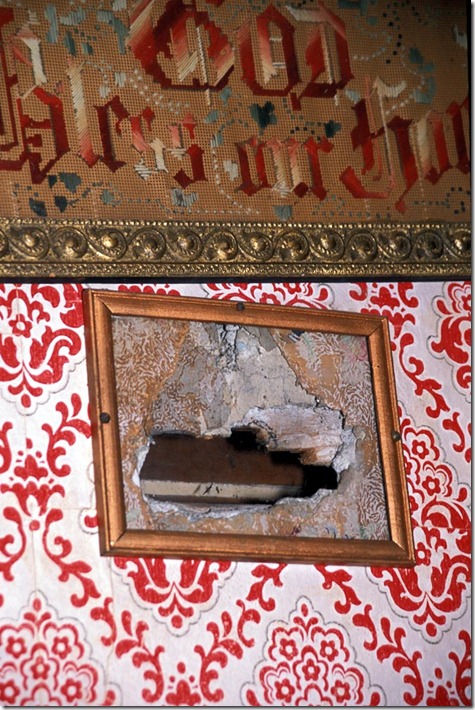

By John M. Flora I stared at the ragged hole in the red-and-white wallpaper and let its significance sink in. That, according to legend, was where the bullet that killed notorious outlaw Jesse James lodged after passing through his head.

![jesse james home[5] jesse james home[5]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/_xPUSJscPh7g/TX_UpX_iG5I/AAAAAAAAJTo/dmfaFm2NEoE/jesse%20james%20home%5B5%5D_thumb%5B1%5D.jpg?imgmax=800) I realized I was roughly where Bob Ford must have stood when Jesse stepped onto a chair to straighten and dust a framed sampler. My right hand flexed as I imagined Ford silently easing his .45 caliber Smith & Wesson Schofield revolver from its holster and firing the fatal shot at his unsuspecting friend.

I realized I was roughly where Bob Ford must have stood when Jesse stepped onto a chair to straighten and dust a framed sampler. My right hand flexed as I imagined Ford silently easing his .45 caliber Smith & Wesson Schofield revolver from its holster and firing the fatal shot at his unsuspecting friend. “The dirty little coward who shot Mr. Howard” flashed through my mind. That’s the only line I remember from the song about Jesse’s betrayal by a James gang member, who was seduced by a $10,000 reward. I’d come to learn about Jesse James and it seemed I was starting at the end of the story.

Road Research

Missouri has always been one of those states I have to ride through to get to more interesting places. Frankly, it was my least-favorite part of the route from my Indiana home and the West. Missouri meant hours of truck-filled, bumpy Interstate 70 with the troublesome traffic of St. Louis and Kansas City at either end.

Counting mile markers to the state line, however, I noticed abundant James-related tourist attractions and began to realize that Jesse James looms large in Missouri history. Since this Jesse James thing represented a gap in my knowledge of U.S. history, I decided to combine a weekend motorcycle trip with some personal research.

Jesse James is a folk hero hereabouts. They name streets, antique malls, museums, and conference centers for him. Hardly the kind of recognition accorded other American bad guys like Billy the Kid, Al Capone, and John Dillinger.

That’s because Jesse fought for the Confederacy (albeit as a guerilla and not as a regular soldier), and came to symbolize the plight of the post-war South, suffering the vengeance of the North and the humiliation of defeat. Tom Goodrich, author of The Day Dixie Died: Southern Occupation 1865-1866, says many Missourians and other southerners saw Jesse as “the last Rebel soldier.”

“The south was under total Union control,” Goodrich said. “So up comes somebody like Jesse James who a lot of people even in Florida and Alabama recognized as a former Rebel soldier, a guy who had not given up… can you imagine what that did for Southern hearts to see this guy … Jesse James was the only viable option to the suffering they were going through all of these years and they were willing to buy into it.”

Whether it was politics or expediency, the James gang targeted banks and railroads -- the most conspicuous examples of Yankee Republican influence in their part of the country.

Following The Trail

The Patee House Museum in Saint Joseph, Mo., is a good place to pick up Jesse’s

trail. The imposing brick structure at the southeast corner of 12th and Penn streets was built as the Patee Hotel in 1858. The house where Jesse James was killed April 3, 1882 was moved to the museum grounds from its original location about a block away in 1977.

trail. The imposing brick structure at the southeast corner of 12th and Penn streets was built as the Patee Hotel in 1858. The house where Jesse James was killed April 3, 1882 was moved to the museum grounds from its original location about a block away in 1977. People come from all over the world to visit the four-room wood frame house and their fingers have worn away the wallpaper and plaster, enlarging the bullet hole to an opening about 3” by 7”. It’s now enshrined in a gold-colored frame, screwed to the wall.

The adjacent parlor features an exhibit based on the 1995 autopsy and DNA research done by Professor James Starrs of George Washington University. It proved to his satisfaction that the body in Jesse’s grave down in Kearney is, indeed, Jesse. The exhibit includes a reconstruction of Jesse’s skull, which came out of the grave in 32 pieces, showing where Ford’s bullet entered behind Jesse’s right ear.

Outlaw Bound

My next destination was the place where Jesse and Frank began a life of outlawry. An hour’s ride down U.S. 169 and Missouri highways 92 and 291 took me to Liberty, and the site of the nation’s first-ever daylight peacetime bank

robbery.

robbery. The Seth Thomas calendar clock in what was once the Clay County Savings Association Bank is perpetually set to the date of Tuesday, February 13. On that day in 1866, a dozen men rode into town by various routes and gathered in front of the two-story brick building on the northeast corner of the courthouse square.

Two men entered and pointed guns at head cashier Greenup Bird and his son, William. After stuffing over $62,000 in bonds, cash, and Federal revenue stamps into a feed sack, they put the Birds into the vault, and rode off.

During the commotion outside the bank, a young boy watching from across the street was fatally shot. His family later received a letter of apology from Jesse James, who said no one was supposed to be injured in the holdup.

The building is now the Jesse James Bank Museum. For a modest admission fee, you can see where an amazed Greenup Bird was confronted by desperados and peer into the vault where he and his son were left.

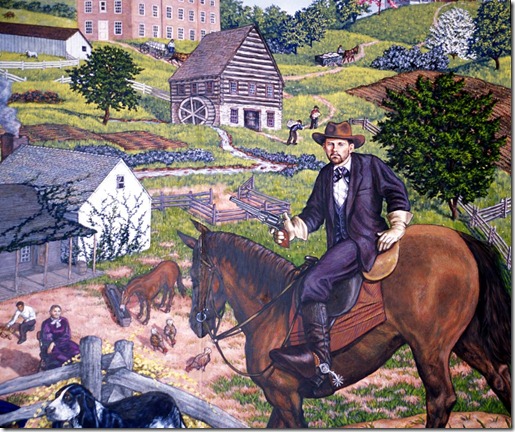

There’s more evidence that Jesse James is fondly remembered across the street. Born and raised up the road near Kearney, Jesse was a Clay County boy, and is immortalized in the 28’-wide central panel of a mural in the Clay County Courthouse. There’s Jesse on horseback, pistol in hand. The James family farm is behind him. And, if you look closely, you can see brother Frank and the James boys’ mother, Zerelda.

There’s more evidence that Jesse James is fondly remembered across the street. Born and raised up the road near Kearney, Jesse was a Clay County boy, and is immortalized in the 28’-wide central panel of a mural in the Clay County Courthouse. There’s Jesse on horseback, pistol in hand. The James family farm is behind him. And, if you look closely, you can see brother Frank and the James boys’ mother, Zerelda. From Liberty On

Lexington was the scene of the James gang’s second daring daylight bank robbery. There are faster ways to get from Liberty to Lexington, but it was a pleasant day and I decided to spend about 90 minutes taking the 46-mile the scenic route up Highway 33 to U.S. 69 through Excelsior Springs.

Jesse and Frank were already outlaw legends when Excelsior Springs got its start as a resort town. In June 1880, a local farmer took the advice of Indians and hunters and let his sickly daughter try the waters at the spring there. After a few weeks of bathing in the spring and drinking its water, the girl was cured of tuberculosis. Others claimed cures for various conditions and Excelsior Springs became known as a place of healing waters.

I took Missouri Highway 10 east out of town, then turned right onto twisty Highway O (I love these letter designations for Missouri’s secondary roads). Winding my way south and east to Orrick and 210, I took Highways T and H to Henrietta. From there, it was a short run on Highway 13 across the floodplain of the Missouri River, over the river on a picturesque iron bridge and up the river’s southern bank to Lexington.

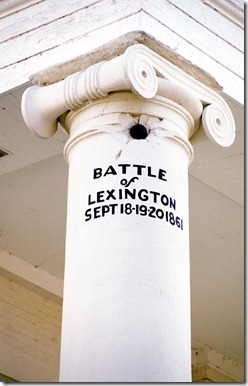

Sharp-eyed visitors will spot a cannonball embedded near the capital of one of

the columns on the Lafayette County Courthouse on Main Street. It’s a relic of the 1861 Battle of Lexington, in which Confederate forces defeated Union troops.

the columns on the Lafayette County Courthouse on Main Street. It’s a relic of the 1861 Battle of Lexington, in which Confederate forces defeated Union troops. Seven months after the Liberty bank job, five riders appeared outside the Alexander Mitchell & Co. Bank on Oct. 30, 1866. Cashier J.L. Thomas, who was alone in the bank, said two men presented a bill to be changed, then forced him to hand over about $2,000.

Today, the bank building at 827 Main Street is Frederickson’s Fine Wines & Spirits. But you can still walk through the big white double doors the holdup men used to exit with their loot. I picked up a bottle of Missouri wine for later and wrapped it in a sweater in my saddlebag. The next stop on my James Gang pilgrimage involved backtracking up Highway 13 for a 9-mile sprint to Richmond.

By the spring of 1867, Jesse and Frank had been joined by their cousins, Cole, Jim, and Bob Younger. They rode into Richmond on May 22, 1867, whooping wildly to scatter the townspeople. The Jameses and the Youngers burst into the Hughes & Wasson Bank and quickly emerged with about $4,000 in a sack. Three other gang members -- Tom Little, Andy Maguire, and Dick Burns -- waited outside, guns drawn.

Unimpressed by the brazen assault, some townspeople started shooting. When the smoke cleared, Mayor John B. Shaw, Jailer B.G. Griffen, and his 15-year-old son Frank lay dead in the street. The Jameses and the Youngers escaped but Little, Maguire, and Burns were captured.

The old bank building at 201 West Main Street is a dental office now. But Dr. Raymond Finke and his wife Susan welcome visitors with an interest in the place.

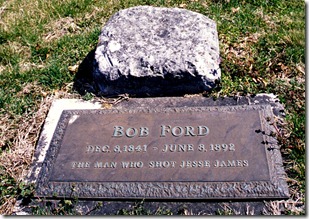

Continuing out West Main Street (also old Highway 10), I found Sunny Slope Cemetery. There, near the crest of a small hill, is a small bronze plaque marking the final resting place of Bob Ford.

Reviled for killing a folk hero, Ford quickly left Missouri with his reward money and became a saloon keeper in Colorado. He was gunned down in a barroom brawl in Creede, Colorado, on June 8, 1892 at the age of 32. His grave marker proclaims his name, dates of birth and death, and the epitaph, “The man who killed Jesse James.”

Reviled for killing a folk hero, Ford quickly left Missouri with his reward money and became a saloon keeper in Colorado. He was gunned down in a barroom brawl in Creede, Colorado, on June 8, 1892 at the age of 32. His grave marker proclaims his name, dates of birth and death, and the epitaph, “The man who killed Jesse James.” Satisfied with a day of chasing the James gang around northwestern Missouri, I picked up Highway 10 west and rode the dozen miles back to Excelsior Springs. There, I checked in at the Elms Resort & Spa.

An Excelsior Springs institution, the Elms hosted President Harry Truman, boxer Jack Dempsey, and gangster Al Capone.

After a hearty Kansas City strip steak dinner in the hotel restaurant and a relaxing soak in the pool-side outdoor hot tub, I sauntered back to my room for a glass of that Missouri wine and a good night’s sleep.

Back On the Trail

Eager to resume my history lesson the next morning, I had a light breakfast, loaded my bike, and followed Highway 10 west out of town five miles to U.S. 69. Turning north, I followed the road another 39 miles north. Although I could have made faster time on Interstate 35 (U.S. 69 crossed its path twice on the way to my next destination), I wanted to avoid the superslab and take my time on secondary roads.

The route took me through Cameron, where members of the James gang boarded a Chicago-bound passenger train the evening of July 15, 1881. I dropped my side stand about 10 miles later at the depot in Winston.

The depot is a museum today. As I studied railroad memorabilia and admired the curved cage designed to keep travelers from burning themselves on the waiting room wood stove, I tried to imagine a second group of gang members making themselves inconspicuous as they waited for the train.

The train pulled out about 10:30 p.m., but traveled less than a mile before two gunmen clambered over the express and coal cars to reach the engine cab. The engineer and firemen jumped to safety and fled, leaving the robbers to halt the train near a trestle where the gang’s horses were tethered.

In the course of the robbery, the gunmen shot and killed conductor William Westfall and also murdered Frank McMillan, an elderly laborer working to reinforce the wooden trestle with stone. Two robbers emptied the express car safe while their confederates robbed the passengers. They galloped into the night with about $800.

Turning back south on U.S. 69, I charted a course for the touchstone of all James gang lore, the legendary home northeast of Kearney. Here, the boys grew up and plotted many of their capers.

I took U.S. 69 about 33 miles south to Highway MM and turned west. About three miles later, I jogged south again on Endicott Road, a twisty little country track that intersects with NE 164th Street after 2.2 miles. Then it was back west again to the entrance to the Jesse James Farm and Museum.

Riding at a leisurely pace, I regarded the fields and farms and wondered how much of this scene Jesse and Frank James would recognize if they could see it today. Surely, the contours of the Missouri countryside haven’t changed much in the 130 years since they haunted these parts. Take away the asphalt pavement, power lines, and utility poles, and you could almost imagine you were riding out to the white farmhouse the locals came to call “Castle James.”

Access to the James house is through the James Farm Museum, a well-organized collection of James and frontier-related displays. It includes a brief film biography of the James family, a detailed James family tree, and such memorabilia as the feather duster Jesse was holding when he was killed. Admission gets you a self-guided tour of the museum and a guided tour of the James farmhouse.

The house, with its rough-hewn floorboards and stone hearth, exudes history. The log cabin portion of the James structure was bought in 1845 by the Reverend Robert James and his wife, Zerelda. Jesse was born here September 5, 1847. The Victorian cottage that forms the front portion of the house was added in 1893.

Frank James surrendered after Jesse was killed and was put on trial for murder the following year. By most accounts, it was a show trial, since the James boys had been folk heroes of a sort.

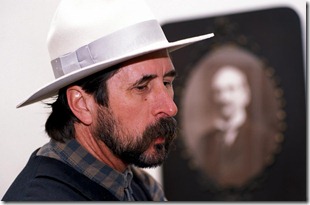

Frank inherited the farm after the death of his mother in 1911 and lived there with his wife Anna and son Robert. He outlived his younger brother by nearly 33 years and died of natural causes in 1915. Heirs sold the property to Clay County in 1978 as an historic site. I chanced to be there on a day when Greg Higginbotham, a James family historian, was playing the role of Frank James.

While he stops short of calling the Jameses 19th-century Robin Hoods, Higginbotham said, “I honestly believe they kind of picked and chose who they wanted to rob. Frank James, in particular, would look very carefully to see who he was robbing. They say he had an eye for a person and might look at his shoes or shake his hand or listen to how he spoke.”

While he stops short of calling the Jameses 19th-century Robin Hoods, Higginbotham said, “I honestly believe they kind of picked and chose who they wanted to rob. Frank James, in particular, would look very carefully to see who he was robbing. They say he had an eye for a person and might look at his shoes or shake his hand or listen to how he spoke.” Higginbotham recounts the story about Frank getting the drop on a man, taking his money and then noticing his victim had rough, callused hands. Frank asked about the man’s work and found he was robbing a farmer. Apologizing, so the story goes, Frank returned the man’s cash with a bit more to boot.

Zerelda James Samuels brought her son Jesse’s body to the family farm for burial beneath a 10-foot-tall stone obelisk in the front yard. The gravesite and house became a major tourist attraction. Mrs. Samuels would let visitors take a nail from the cabin wall for a small fee, hammering in new nails for the next batch of tourists after the previous group left.

But Zerelda fretted that grave robbers might steal her son’s remains and put them on exhibit at fairs and circuses – a fate that befell the corpses of some other outlaws of the period. So, in 1902, Jesse James Jr. exhumed his dad and reburied the body next to that of Jesse’s widow in the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Kearney.

I found the cemetery on the south side of Highway 92 on the west edge of Kearney, across the street from the Big V Country Mart. I easily negotiated the hard-packed gravel lane into the cemetery, dismounted, and searched down the gentle slope of grave markers.

I found the cemetery on the south side of Highway 92 on the west edge of Kearney, across the street from the Big V Country Mart. I easily negotiated the hard-packed gravel lane into the cemetery, dismounted, and searched down the gentle slope of grave markers. Jesse’s wife, Zerelda Mimms James, a first cousin named for his mother, died on November 13, 1900. So her presence in Mount Olivet Cemetery made it a logical final resting place for Jesse.

Their graves are marked with a simple granite stone, laid flush with the ground. Visitors have chipped away fragments of the stone around the carved letters and numbers. A vertical slab in the style common to Civil War veteran graves recognizes Jesse’s time with Quantrill’s Raiders.

This is the grave Professor Starrs reopened in 1995 for DNA tests. The excavation also yielded a Civil War-era bullet thought to be the one Jesse took in the chest when he tried to surrender at war’s end.

Tom Goodrich’s words came back to me: “Jesse tried to surrender along with other rebel soldiers in June, 1865, in Lexington. He ran into a Union picket post, and they shot him as he was flying a white flag – shot him just above the heart. Jesse recovered, but I think he said from that day forth, ‘That’s all the surrendering I’m going to be doing in this lifetime.’

“Jesse could not come back and live like a normal person anymore. So rather than be run around from pillar to post like a lot of his former comrades, he went to a life of outlawry,” Goodrich said.

While nobody knows the exact numbers, it’s a safe bet that Jesse’s legend has put more tourist dollars into the pockets of his fellow Missourians than he ever dreamed of taking from the banks and railroads of his day.

SOURCES

The Elms Excelsior Springs, Missouri

800-THE-ELMS

www.elmsresort.com

James Farm Museum

Kearney, Missouri

816-628-6065

Jesse James Bank Museum

Liberty, Missouri

816-781-4458

Patee House Museum/Jesse James Home

St. Joseph, Missouri

816-232-8206

www.stjoseph.net/ponyexpress

2 comments:

I find it curious that your extensive journey and investigation of certain facts takes no notice or question of the fact that Robert Fords grave marker is incorrectly dated by 20 years. The marker say's he was born in 1862 but he short Jess in 1882 and died in 1892 at the age of 30. His true birth date was January, 31 1862 but the marker reads December 8, 1841. Do you have any information on this massive incorrect mistake on the man's behalf. Admittedly a coward, but you might think his grave marker was correct, unless they moved the wrong body to Richmond Cemetery from Creede County Cemetery.

Don't know. Don't care.

Post a Comment